PROFILE

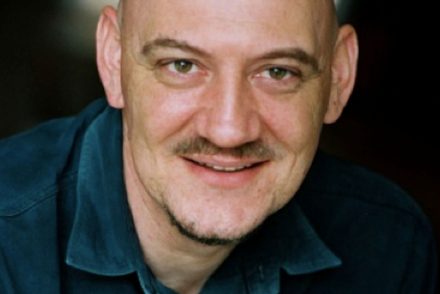

Meg is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing and English Literature at the University of the Western Cape, where her responsibilities include, UWC CREATES, the first multi-lingual Creative Writing programme in South African Higher Education. She has published academic and creative work in South Africa, the UK, the US and Vietnam. Her two works of fiction, This Place I Call Home (2010) and Zebra Crossing (2013) were praised by critics, and Zebra Crossing was selected by the Cape Times as one of the ten best South African books published in 2013 and was Long Listed for the 2014 Sunday Times Literary Award. In 2015 it was chosen by Booker short-listed author, Sunjeev Sahota for the Guardian newspaper in the U.K, as one of the Top 10 books about migrants. For 2016, Meg was asked to act as Senior editor for New Contrast, South African oldest literary magazine. Her new novel, The Woman of the Stone Sea, which is set in a West Coast fishing village and features an IsiXhosa water maiden (umamlambo) and a local crayfish fisherman is due for publication in 2019.

Meg is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing and English Literature at the University of the Western Cape, where her responsibilities include, UWC CREATES, the first multi-lingual Creative Writing programme in South African Higher Education. She has published academic and creative work in South Africa, the UK, the US and Vietnam. Her two works of fiction, This Place I Call Home (2010) and Zebra Crossing (2013) were praised by critics, and Zebra Crossing was selected by the Cape Times as one of the ten best South African books published in 2013 and was Long Listed for the 2014 Sunday Times Literary Award. In 2015 it was chosen by Booker short-listed author, Sunjeev Sahota for the Guardian newspaper in the U.K, as one of the Top 10 books about migrants. For 2016, Meg was asked to act as Senior editor for New Contrast, South African oldest literary magazine. Her new novel, The Woman of the Stone Sea, which is set in a West Coast fishing village and features an IsiXhosa water maiden (umamlambo) and a local crayfish fisherman is due for publication in 2019.

CREATIVE WORK

Extract from The Woman of the Stone Sea (novel)

When Hendrik reaches the cove he turns the engine off. He is close enough to row and there is enough light to see. If you are not careful, even with good visibility, the current can carry you along and before you know it, trouble. A boat’s wooden bones can smash as easily as ‘n babatjie’s. But he has being doing this his whole life. He knows what he is doing. He takes the oars out from under their tarpaulin and drops them into the oarlocks. He positions the boat so that he is sculling at a right angle to the waves. It is easier this way. It is harder for the waves to carry you into the rocks if you take them at an angle. But jissus it is hard work. His shoulders feel the strain. He is getting old, and not just in his body as he rolls over the waves towards the shore. The oars splash. Icy seawater sprays up, hitting his bearded cheeks and aching hands.

When the water is finally shallow enough for him to jump out and drag the boat the last few meters onto the beach by its tow rope, he does. The ocean, she wants his boat and seems to pull it away from him, back towards open water, but he holds fast. He still hasn’t seen anything.

It is only when he has pushed the boat so that it is safely beached, and buried the anchor into the sand for good measure, that he catches sight of her. No, not his Rebekkah. The back of a black woman down at the water in a cradle of rocks. The cradle of rocks around her meant he could not have seen her from the sea. He is disappointed. Ja, he is not ashamed to admit it. Even after five years it is the belief that she will come back to him, that gets him out of bed each morning.

‘Meisie! What are you doing out here?!’ A gathering wind scoops up his bitter shouts, ‘Hey!’

She isn’t moving. Is she ignoring him? Or maybe she does not speak Afrikaans. Another fokken darkie inkommer, Hendrik thinks, an outsider not born in the village. Last year at election time, the ANC bussed what seemed like hundreds of them in. Darkies who could not speak a word of Afrikaans or even English. Darkies who they say, came all the way from the Eastern Cape. The government wanted them to sway the vote, but they failed. These days this village is loyal to the Democratic Alliance, a political party that the villagers say, actually cares a fok for the Coloureds and whites.

So what is she doing here in the Reserve? Hendrik wonders as he walks towards her through the shivering fynbos. Gryp, that is all these darkies know how to do.

‘Meisie! Girlie! What are you doing here? Private property. You can’t squat or build your shack here.’

They bring crime too. Murder, robbery, verkragting.

It is completely light now. The water has that brilliant early morning sparkle and he can see her clearly. With a grunt Hendrik pushes through another scrub bush. She is slumped over, body half in and half out of the water. If he were drunk, he would think he was seeing things, but he is sober.

She is naked. Naked but, Hendrik’s eyes travel down. Lewende Vader. Hendrik stands gawping, his mouth open and closing in silent shock, like a freshly snagged snoek.

REFLECTION

The Woman of the Stone Sea builds on questions and themes, which I began to explore in my previous novel, Zebra Crossing. These include: what does home mean in a South African context; what is the relationship in this country between the supernatural world and the so called ‘real’ and how can we navigate our painful history and disappointing present in order to carve a noble and hopeful future. In the novel we encounter Hendrik, a coloured fisherman who lives in an unnamed village on South Africa’s West Coast. At the start of the novel Hendrik attempts to commit suicide because he is unable to come to terms with the fact that he has been abandoned by his wife (Rebekkah) who walked into the ocean several years earlier and has not been heard from or seen since. However, his suicide attempt fails and he wakes up sodden but alive in his own home. Convinced that he felt and saw something in the ocean where the attempt was made, he returns to the cove the next day. What he finds is not his beloved Rebekkah, but a umamlambo, an isiXhosa water maiden. The extract is taken from that scene.

During the rest of the novel, the reader is left guessing whether the mamlambo is in Hendrik’s mind (a psychological delusion brought on by his loneliness and grief) or whether her presence is real. The unlikely relationship between Hendrik and water maiden or vis vrou, as he calls her in his mother tongue Afrikaans, will hopefully provoke the reader to consider the enduring interracial prejudices and tensions between South Africa’s non-white communities (in this case the coloured and isiXhosa ones) but also a shared history which is often overlooked.

PUBLICATIONS

The Woman of the Stone Sea (RandomHouse/Penguin) forthcoming 2019

Zebra Crossing (Oneworld and RandomHouse/Penguin) 2014 and 2013

This Place I Call Home (Modjaji Books) 2010